[ad_1]

Right this moment, we obtained one other jobs report displaying that the labor market stays pink sizzling. Unemployment fell to three.4%, a 54-year low. Job progress was 253,000, which is properly above pattern and properly above pre-report estimates.

By far an important information level, nonetheless, is the expansion charge of common hourly earnings. Nominal wages grew at a 6% annual charge in April, properly above expectations. (The 12-month progress charge ticked up from 4.3% to 4.4%.) For a Fed that’s attempting to sluggish the expansion in combination demand, that is unhealthy information. For the needs of financial coverage, wage inflation is the one inflation charge that issues.

Why does the economic system stay so sizzling, regardless of greater than a yr of “tight cash”? Is it lengthy and variable lags? No. A really tight cash coverage reduces NGDP progress nearly instantly. The precise drawback is a misidentification of the stance of financial coverage.

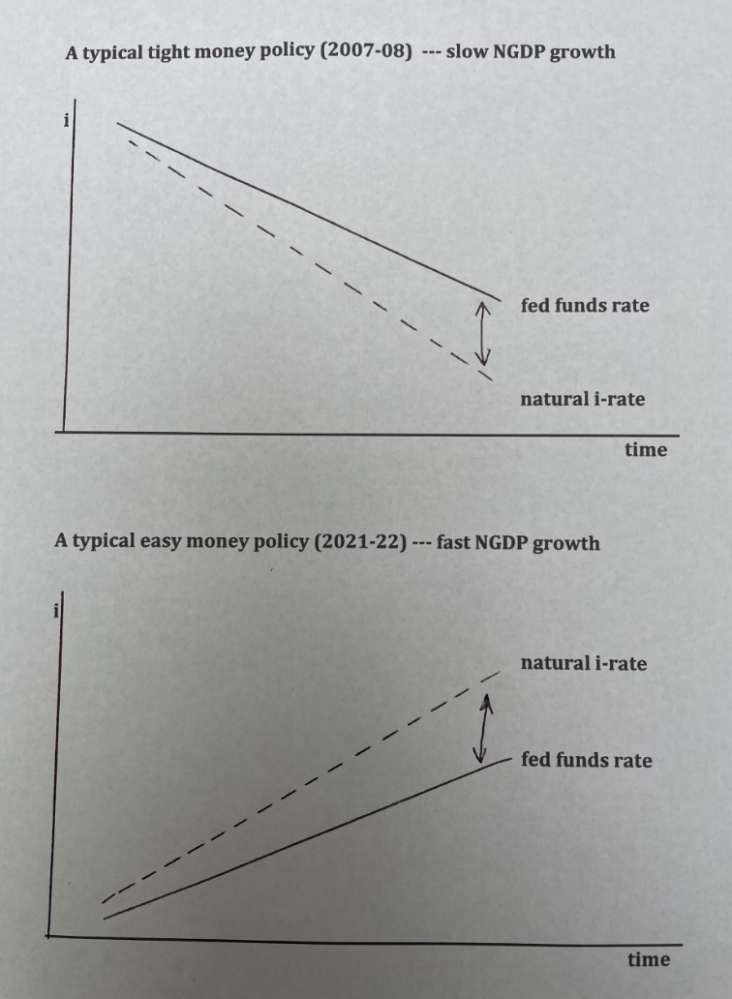

I’ve mentioned this subject on quite a few events, however folks don’t appear to be paying consideration. So maybe an image would assist. Within the two graphs beneath I present typical examples of a good cash coverage and a straightforward cash coverage. Word that what actually issues is the hole between the coverage charge (fed funds charge) and the pure rate of interest.

It’s not all the time true {that a} interval of tight cash is related to falling rates of interest, however that’s normally the case. Does that imply the NeoFisherians are right—that decrease rates of interest symbolize a good cash coverage? No. For any given pure charge of curiosity, decreasing the coverage charge makes financial coverage extra expansionary. That reality is evident from the way in which that asset markets reply to financial coverage surprises. However when the pure charge is falling (typically as a consequence of a earlier tight cash coverage), the coverage charge normally falls extra slowly. To make use of the lingo of Wall Road, the Fed “falls behind the curve.”

The alternative occurred throughout 2021-22, when the Fed raised charges extra slowly than the rise within the pure rate of interest. On this case, it wasn’t a lot the tempo of charge will increase, which was pretty sturdy, it’s that they waited too lengthy to boost charges, by which period the pure rate of interest had already risen sharply.

P.S. The pure charge can’t be straight measured; we infer its place by taking a look at NGDP progress. That’s why I ignore rates of interest and deal with NGDP.

[ad_2]